J.J. Thomson and the Publication Conflagration

Peer review can be tough. Sometimes minor revisions aren’t so minor and major revisions turn out to be sugar-coated rejections. Ultimately everyone gets a bad review at some point. J.J. Thomson, of electron and plum pudding model fame, certainly got a few and in at least one case either reacted exceptionally poorly or was the victim of a slightly unfortunate and mildly embarrassing accident.

While he was still proving his experimental chops as the newly minted head of the Cavendish laboratory and over a decade before his discovery of the electron, Thomson published two articles in the premier journal of the Royal Society of London, Philosophical Transactions. Of these articles the first, published in 1885, is entitled “On some Applications of Dynamical Principles to Physical Phenomena,” while the second, published in 1887, dropped the “On” and appended a “Part II.” As the titles suggest, Thomson was pretty excited about explaining a range of physical phenomena with reference to dynamics instead of just deducing them from the Second Law of Thermodynamics as was common at the time. If this dynamical analysis was successful, the mechanical assumptions that accompany this kind of analysis would strongly suggest at a deep underlying similarity between these phenomena. As he readily admits, at that time most physicists, especially British physicists, were happy to assume that essentially all physical phenomena were fundamentally mechanical and thus susceptible to dynamical treatments in keeping with the conservation of energy. So basically, Thomson spends these two papers describing various elastic, electrical, magnetic, heat, and in the second paper chemical phenomena in the terms of Lagrangian dynamics.

The Royal Society keeps referee reports and correspondence related to those reports (referee reports are the formal reviews of prospective articles written by what you hope are carefully chosen expert reviewers). This is how we know, for example, that Edward Routh, famous Cambridge tutor and the guy who beat Maxwell in the 1854 Tripos exam, and William Thomson, i.e. Lord Kelvin, both thought the first of J.J.’s papers was fit for publication in the Transactions. It’s also how we know that the reports connected to J.J.’s second dynamical paper were not so straight forward. This is particularly odd given that it was Routh and Kelvin who were again called upon to review “Part II.”

Routh for his part didn’t change his opinion much between his two reviews. In both of his reports he opens by admitting to not having finished reading through either paper, although he insists that he has read enough to recommend both for publication. In his review of the first paper, Kelvin makes a few recommendations for changes, but is similarly happy to recommend the paper for publication. Kelvin’s review of J.J.’s second paper is decidedly less enthusiastic.

This review immediately stands out among the others 1887 reports; first of all, it looks like it’s written on tissue paper (more on that in a moment). Besides the low quality of paper, the report is almost comically pessimistic. Kelvin argues that J.J.’s dynamical project is questionably dynamical and uses “indefinite” methods and he’s displeased by the lack of discussion of foundational concepts and definitions (which I must admit I would also have appreciated). Indeed, Kelvin recommends that the entire paper be scrapped and any of its novel inventions rederived in more exacting ways. Not only does Kelvin recommend that the paper not be published, he also spends a paragraph expressing his regret in having recommended Part I.

The next entry is not actually a report at all, rather it is a combination apology to the editor (Lord Rayleigh) and response to Kelvin’s negative review. J.J.’s letter begins,

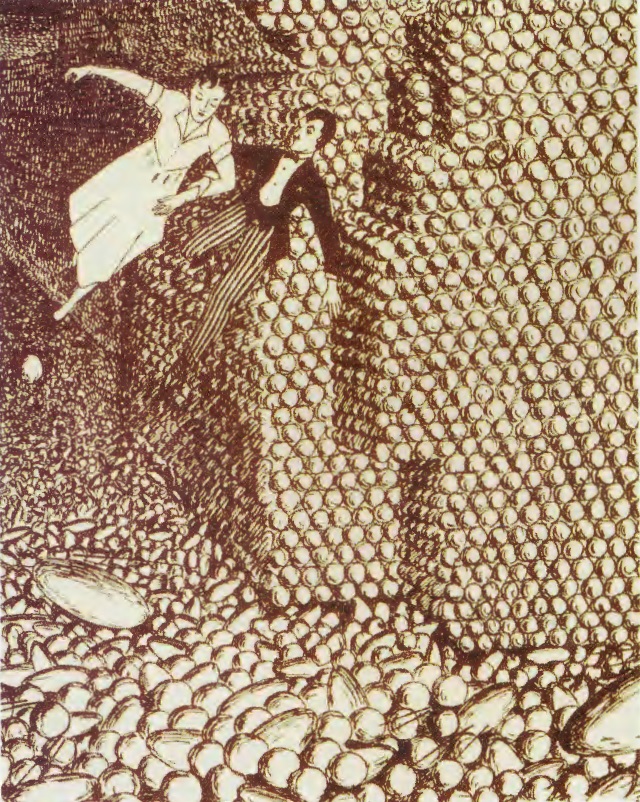

I am very sorry to say that an accident has happened to Sir William Thomson’s report on my paper. I left it on my desk and last night whilst I was in another room a shade fell from a candle and caught fire as it fell, burning a great many papers on my desk and the report among them it was so badly burnt that I was not able to decipher it.

Now I’m not saying that J.J. intentionally set what was likely a totally unexpected and mostly unfair review on fire, I’m just saying there was definitely motive. Maybe it did happen as he tells it, and if so I can’t imagine a way to phrase it that would make it sound much more believable. As it stands, J.J.’s letter is basically a long winded way of saying “Sorry Kelvin’s report accidently got burnt, I remember it anyway, and his criticisms were overly general, hypocritical, and largely missing the point.”

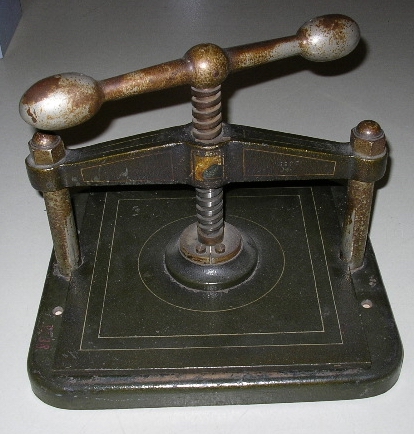

But wait, if Kelvin’s original report was burned (intentionally or not) how does the Royal Society have a copy, albeit one on crappy paper? Well the next letter is from Kelvin, and while it reiterates most of the same criticisms about J.J.’s second dynamical paper not being dynamical enough, it also notes that he kept a “press copy” of the original report, which he sends with this new letter.

Before there were photocopiers there were copy presses. Basically, you wrote your original letter in special ink and then used a screw press to smash it together with some tissue paper. Really boring mystery solved.

So what about J.J.’s paper? Routh, despite not having properly read it, was in favor of publishing and Kelvin was not exactly a supporter. I already revealed it was published, so what happened? It seems that around the same time Routh and Kelvin submitted their reviews it was also sent out to the British chemist Herbert McLeod. In what is a lesson to all those who read academic papers, Herbert McLeod, who notes at numerous points that he feels unqualified to judge the paper and “wish[es] it had not been referred to me,” who, despite offering tepid approval of the paper, never actually utters the magic words of recommendation, appears to be responsible for halfheartedly nudging the paper over the publication goal line.